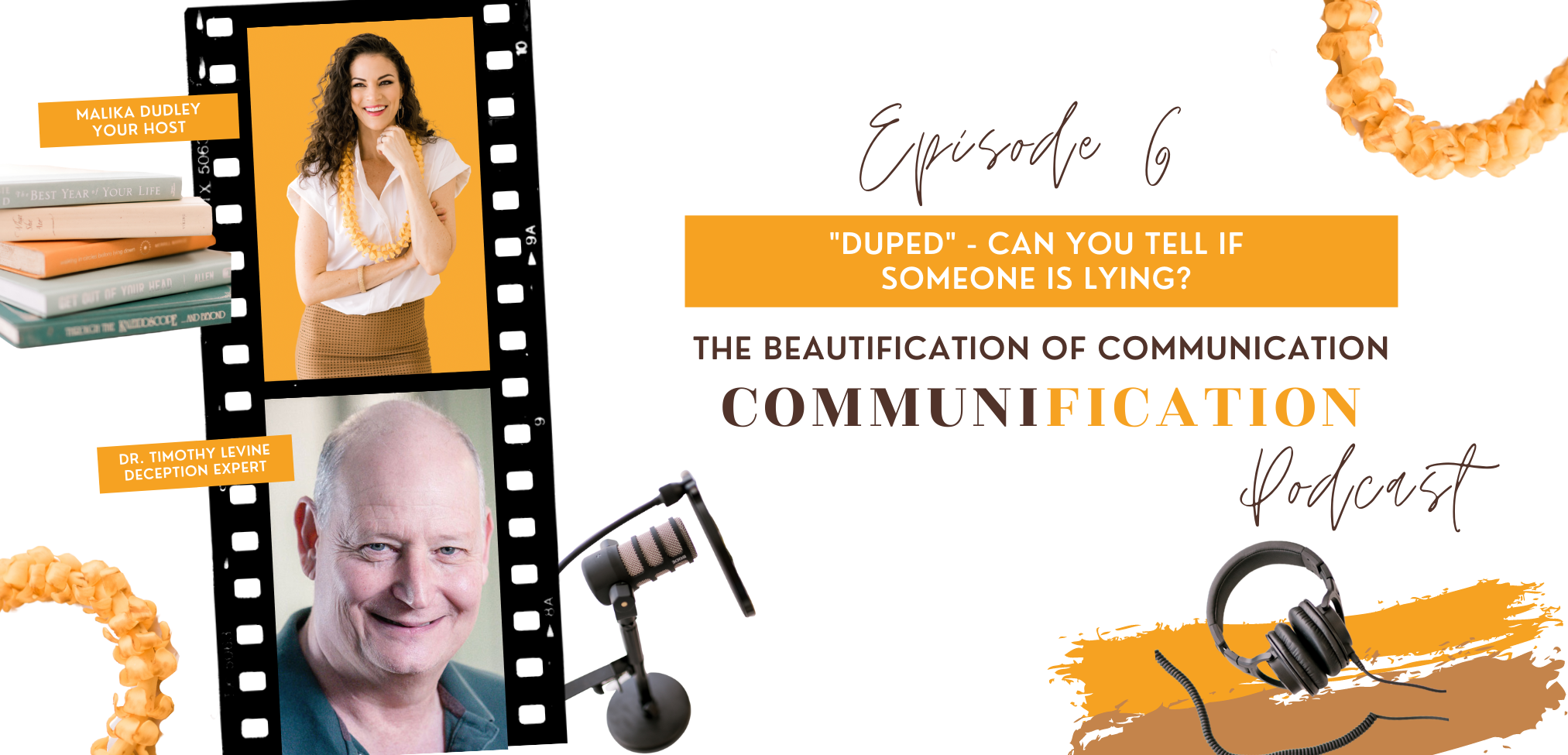

Ep. 6: Lying & Deception: Have you been duped? We break down the deception research with Dr. Timothy Levine

Below you will find the show notes for “Episode 6” of the Communification Podcast.

Mahalo for listening! Welcome to the ‘ohana!

MAHALO to Pukalani Superette for supporting the Alzheimer Association of Hawaii, Maui Video & Marketing for supporting the Maui Food Bank, and Texaco in Hawaii for supporting HUGS Hawaii. Tap the links to find out more about these non-profits and generous local businesses.

In this episode we talk to Dr. Timothy Levine about deception. He introduces us to the theory he developed - Truth Default Theory - and, shares interesting insights from deception research in the communication field. You will learn why people lie, how to best detect lies, and why we are SO BAD at deception detection (especially when we rely on nonverbal cues).

Main takeaways

You can be honest and not be rude. You can be honest and protect your privacy. It’s not all or nothing.

There are both negative and positive consequences to deception.

Most people are honest most of the time.

Demeanor is not diagnostic for most people. You just can’t tell if someone is lying by their body language alone.

Deception in relationships is both harder and easier to detect.

The best thing you can do to detect deception is to fact check.

Time codes

GUEST: Dr. Timothy Levine

[00:06:39] HOW AND WHY DR. LEVINE GOT INTO DECEPTION RESEARCH

[00:07:42] DEFINING DECEPTION

[00:08:15] DEFINING HONESTY

[00:09:29] GOALS AND MOTIVES OF DECEPTION

[00:12:01] EVERYONE IS HONEST WHEN IT’S NOT PROBLEMATIC - WE DEFAULT TO TRUTH

[00:13:52] NEGATIVE IMPACTS AND RELATIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF DECEPTION

[00:14:39] POSITIVE CONSEQUENCES TO DECEPTION

[00:16:06] WHAT IS TRUTH DEFAULT THEORY?

[00:25:47] DECEPTION AND TECHNOLOGY - NO NONVERBAL CUES?

[00:27:18] IDENTITY DECEPTION

[00:33:22] BUTLER LIES

[00:35:42] LISTENER QUESTION FROM IAN

DOES THE TYPE OF RELATIONSHIP YOU HAVE WITH A PERSON HELP OR HINDER DECEPTION DETECTION?

Dr. Timothy Levine bio

Timothy R. Levine is Distinguished Professor and Chair of Communication Studies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Levine’s teaching and research interests include deception, interpersonal communication, persuasion and social influence, experimental research design, measurement validation, and statistical conclusions validity. He has published more than 140 journal articles. His research has been funded by the National Science Foundation, Department of Defense, and Department of Justice and his work has received press coverage from New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, NBC, CNN, Discovery Chanel, and National Geographic. His most recent book, Duped: Truth-Default Theory and the Social Science of Lying and Deception, published in 2020 by the University of Alabama Press, details his 30-year program of research on deception leading to the development and testing of Truth-Default Theory.

EPISODE 6:

Duped - Can you tell if someone is lying? We break down the deception research with Dr. Timothy Levine

Malika:

Aloha Dr. Levine, thank you for joining us today for the Communification podcast. Welcome to the show.

Dr. Levine:

Thank you. Happy to be here.

Malika:

Well, This topic is a doozy and we'll tackle it in a moment, but first, would you please share with all of us how you became a deception researcher and expert and where your passion on this subject comes from?

HOW AND WHY DR. LEVINE GOT INTO DECEPTION RESEARCH

Dr. Levine:

Sure. I started getting into deception research in graduate school. I had a bunch of professors who were interested in it and I got involved in some of their research. It's not what I went to graduate school to study, but as I started learning more about it, every study seemed to raise more questions than they answered. And I'm a little tenacious. So I kept kind of trying to run down loose ends and I really like puzzle solving. I'm a naturally curious person and deception, surprise - surprise - things aren't what they seem in deception. So it was a great opportunity for me to try to satisfy my own curiosity. My research has been this kind of 30 year endeavor to kind of make sense out of findings.

Malika:

Well, to begin, I thought before we get into the impacts of deception on our communication and in particular via technology, because this season is all about communication and technology, could you define deception for us just to lay the foundation?

DEFINING DECEPTION

Dr. Levine:

So deception would be knowingly intentionally or purposely misleading another person. I get you to believe something that is not the case, or it can be simply, I can keep you from knowing something that is the case.

Malika:

So like omission or evasion or equivocation, which is when we are ambiguous about things, or generating false conclusions but you know things to be true.

Dr. Levine:

All of the above. Yes as well as the outright lie.

DEFINING HONESTY

Malika:

Got it. Why don't we also define honest communication? I think that's important.

Dr. Levine:

So honesty as kind of absent this deceptive purpose or intent.

I would differentiate honesty and bluntness. You can be honest and not be rude. You can have some privacy and still be honest. So you don't have to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth and every little detail.

But being honest is I'm not misleading you with any kind of purpose, intentionality, or function to it.

Malika:

I like that. That makes me think a little. So what are some examples of deception?

Dr. Levine:

Oh, there's so many, so I'm sure what comes to mind probably first for people are political deceptions. Politicians lying in order to get their vote or people selling you stuff or for fraud cases. People do things that they shouldn't do, and they want to hide those bad things. You know, maybe marital infidelity would be another obvious example, but people can also just not want to go there in conversations and steer people away. They can not want to hurt people's feelings.

Malika:

I think that leads us right into the question of what are the goals and motives for deception.

GOALS AND MOTIVES OF DECEPTION

Dr. Levine:

One of the insights is there are goals that are unique to deception that distinguish deception from honesty.

So if I want to make a good impression on you for example, or if I want to make a good impression on your audience, I can do that honestly, through, you know, hopefully I'm brilliant sounding and I'm accurately portraying my ideas and my research, but I could also do that fraudulently. I could make up qualifications that I didn't have, maybe a good example would be going in for a job interview.

And you really want that the job.

So both the honest and the dishonest person have the same goals. They want the job. It's just, if the truth works out well, then you can present it honestly.

But if you really want a job and you just don't have the qualifications, you might be tempted to be dishonest.

So dishonesty happens when there's a mismatch between the goals and the reality of the situation. So if the truth works well just about everybody will be honest. If I'm happy to be here, I will tell you very sincerely I'm happy to be here. Right now, I would never lie and say, oh yeah, This is such a drag when I'm actually having fun.

Nobody tells that lie.

Malika:

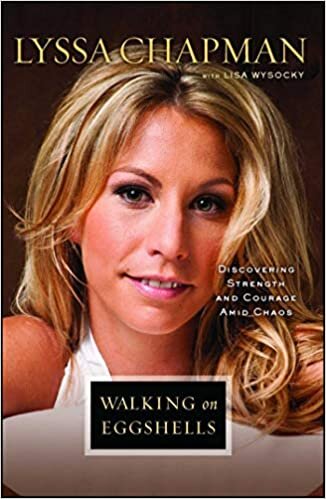

I love you say this over and over again in your book “Duped” - that deception happens when the truth is problematic.

Dr. Levine:

Absolutely.

Malika:

And so I did have a discussion on clubhouse just prior to doing this because I wanted to just kind of get the juices flowing and hear some anecdotal stories, just hear what people have to say about their real lived experiences and what came up a lot was people saying that they lie for “self-preservation” and the way that they described this... so Josh and Liz in particular, describe this as sometimes we need to tell untruths to keep the peace or in extreme cases for safety reasons.

So there was an example of someone confronting someone else about infidelity, but this person came to the person's home and was in front of the children. And he felt like he had no choice for safety reasons than to lie to this man and say, no, no, no that didn't happen, even though it did. This man also said though, that if he had been confronted in a safe space, like say via email or a phone call, that he would have just come out and told the truth.

So whether it was a white lie or infidelity or murder, you know, there's always a motive to lie. You lie because the truth is problematic. There's a reason for it. And if you don't have a reason to lie, then there's this truth default, right?

EVERYONE IS HONEST WHEN IT’S NOT PROBLEMATIC - WE DEFAULT TO TRUTH

Dr. Levine:

Yes. Exactly. You know, I've done some experiments on this and put people in situations where the truth is either problematic or not.

And when it's not problematic, everybody's honest, but even when you're tempted or where you have some motive to deceive, not everybody will deceive.

Some people will be honest, even though the truth doesn't work in their favor. And in my research that it's kind of about one third of the time people are honest even when they have a good reason not to be so, so just because you have a motive to deceive doesn't mean you're going to be deceptive, but if we don't have a motive, unless there's just some real mental illness or something, you're going to invariably be honest.

Malika:

That is so interesting. And it's a good point to bring up that people will tell the truth because maybe it comes back to character and values. This is who I am, and "ahh" it is problematic for me to tell the truth in this particular instance, but this is who I am. I need to be true to my values.

Dr. Levine:

And doing that, I think really is a good communication strategy. A couple of years ago, maybe the biggest mistake in my career, in my job. And I could've blamed it on somebody else, but instead I went to my boss and I owned up to it, even though maybe it wasn't all my fault, it was at least partially my fault, but I totally owned it up. Came clean, sincerely apologized, promised (a) I would do my best to make it right, and (b) I would never make the same mistake again. And, I think I gained a lot of credibility with my boss for doing that.

NEGATIVE IMPACTS AND RELATIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF DECEPTION

Malika:

Yessss. Okay. Let's kind of switch gears just a little bit. This might seem like an obvious question, but what are some of the negative impacts or relational consequences, since we're talking about communication and deception, that pop up in the literature and the research about the deceiving people?

Dr. Levine:

Well clearly the big one is trust, cause when you find out you've been lied to by somebody, why should you believe the next thing they say? But as it turns out, it's not mere deception that's important, but it's what you're lying about.

First off, the little lies almost never come out anyways. You know, if people gets fooled about a surprise party, they're not going to hold that against you, but the big, big, bad lies, and it's not just you're lying, but what you're lying about and that can erode trust.

And it's just very hard to be close to people you don't trust and trust is hard to build and, and easy to squander.

Malika:

Yes, and are there positive consequences to deception? I suppose it would be with those little lies?

POSITIVE CONSEQUENCES TO DECEPTION

Dr. Levine:

Yeah, all the good things I think that happen because of deception are kind of the social smoothing. We started to go there a little bit earlier, to avoid fights. There's some topics that, you know, if you bring it up, it's just going to generate bad feelings and there's really kind of just no reason to go there.

Malika:

And that's okay.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah. And I think maintaining privacy, I think there's a lot of value to maintaining privacy.

Malika:

Oh, that's so interesting. I actually interviewed someone a while back and it was an influencer who has millions of followers and she was saying that they have actually outright lied to their followers to say that they live somewhere that they don't, for safety reasons. And, well, to be honest, because you know, this will go out at a different time. I'm actually going on vacation in a couple of days and whenever I go on vacation, I put out a thing on my Instagram because I do have thousands of followers as well that says, "oh, thank you, Michelle, for house sitting."

Because we know that people take advantage, especially online with the affordances of social media and computer mediated communication, where it's accessible. You can see what people are doing in real time. And so sometimes there's a place for not showing things in real time. I know that the Kardashians don't tend to post their things when they're at wherever they're at, because it is a safety issue.

Dr. Levine:

Absolutely.

WHAT IS TRUTH DEFAULT THEORY?

Malika:

All right. So enter TDT, what is it? And what is the purpose of this theory?

Dr. Levine:

TDT stands for Truth Default Theory. And it's all about the truth default, which we've already talked a little bit about, but more than that, and its real purpose is to make sense out of findings that otherwise didn't make sense.

In my read of the academic research on deception, there were lots of theories out there. But all of them were somewhat empirically challenged in that the research just didn't really line up with what the theory said very well.

So this was an effort to put together an account that would bring together things and make, make the findings form a nice mosaic, where all the pieces fit together and, things that were previously puzzles made sense to try to understand the topic and the role of deception, our honesty and human communication and human relations.

Malika:

What are the tenants of TDT? What can we learn from TDT?

Dr. Levine:

We can start with the truth default, which has two sides to it. The side we've been talking about, where when we communicate, we generally default to honesty, unless we have a reason to lie, but TDT really started on the receiver side where we tend to believe other people, unless we have a reason not to. The keyword is trigger.

So unless there's some kind of trigger the idea that somebody might be deceiving us just never even comes to mind.

Malika:

So those triggers, and I have them listed here are, projected motive for deception, behavioral display associated with dishonest demeanor, a lack of coherence in the message content, a lack of correspondence between communication content and reality, and information from a third party warning of deception.

Dr. Levine:

So people lie for a reason. People might also know that other people lie for a reason. For example, if you're trying to sell me something, I might be more on guard for deception. So if I realize you might have a reason why you would lie to me then deception is more likely because that's when people do in fact lie.

Malika:

Right? And then the behavioral displays associated with dishonest demeanor. I was really interested in this part of the book because you talk about not just dishonest demeanor, but also honest demeanor, and the matching of your demeanor to actual veracity or truth telling. So can you tell us a little more about that?

Dr. Levine:

Sure. This is what got Macolm Gladwell interested in my research. Almost all throughout the history of deception research, people have always been looking for non-verbal things as tells that would giveaway deception. And my ideas are kind of, there's two key elements. First tells don't travel alone, but there's a whole kind of package in how you come off. And I called this demeanor.

So rather than just eye contact or just acting nervous or just hesitancies, it's the whole package of how people are coming off. And second, how you come off is completely independent or uncorrelated or unrelated to whether you're actually honest or not.

So the friendly extrovert people tend to believe, and the person who comes off a little bit like they're on the spectrum may seem dishonest, but of course, just because somebody is nervous or anxious, or hesitant, or a little off, or lacks a little social skills, or is a little bit introverted, avoids eye contact - doesn't mean they're dishonest.

And similarly, just because people are smiling and nodding and being friendly and engaged and outgoing doesn't mean they're honest, but people mistake friendly extroverts for honest, trustworthy people.

Malika:

That reminds me or makes me start thinking about the few prolific liars that give us that slightly above chance of detecting deception based on non-verbal cues. Can you talk about that a little more?

Dr. Levine:

Sure, but there's two things going on. There's the few prolific liars, and then there's a few transparent liars. So a few prolific liars is the idea that most deception is told by a very few people who lie a whole lot. So research on how often people lie, finds that people lie on average once or twice per day. And this might imply that everybody lies kind of once or twice per day, but that's not at all the case.

What's actually the case is most people don't lie at all in any given day. And there's a few people who tell a whole bunch of lies five for more a day and they pull the average up. So really all we need to be on guard for is those profilic liars and not the honest majority.

My latest findings that came in after the book was written, found that about 75% of the people are honest majority and they tell at most two lies a day, vast majority of days are zero to one. But there are this kind of 15% or so of people who routinely tell five or more a day.

Malika:

I was just thinking about the transparent liars. Maybe that's where the non-verbal camp comes from? Because there are people that you can tell they're lying because they are averting their eyes and acting really strange. Sometimes you can tell when someone is lying because of their non-verbals, but not much more than chance.

Dr. Levine:

Exactly. So maybe one out of every 15 or one out of every 20 people, just can't lie.

People start lying maybe, they have the cognitive ability to tell really simple lies, in the three to five range, they get better at it between five and 10 by mid-teenage years, most people can lie pretty seamlessly.

And you just can't tell, but there's a few people who, for whatever reason, just can't. In my research, I had one woman that when she started lying, you could just see her face turn red.

Malika:

Oh, poor thing.

Dr. Levine:

There's another that just kind of broke out into hysterical laughter.

Malika:

Oh gosh. We all know one. We all know one and you know, maybe that's why it's so easy to believe the nonverbal theories on deception. And then the media. I put out a question to my following - how can you tell someone's lying? And what I received back was a slew of different answers, which were really interesting. Here, I'll read them to you. Now, one person said. "Lie to me." And you had talked about "lie to me" in your book. And she was like, well, there was that show. I just loved it so much “lie to me.” And it was all based on research and dadadadada. And so I ended up telling her what your book said, but also Erica said contradictions in their story and that they would need more detail. Lynnie said liars offer up excessive amounts of details and explanation. Lucas said, people usually say lack of eye contact, but that could just mean social anxiety or shyness humans are on average bad at knowing if someone is lying.

Michelle said when the eyes blink rapidly. Megan and Courtney both said, eye contact, body language, facial expression. And Kilikiana said that if they act weird or different, if it's not their normal way of speaking, and these were the answers that it got to the question - how do you know if someone is lying?

Dr. Levine:

So there's no evidence for any difference in eye contact at all. Blinking is nondiagnostic too. Details actually works the other way around. On average, honest people tend to have more details than truth tellers, but this one's really tricky because details also depend on how good your memory is. How long ago the event happened, how vivid the memory was. There's all kinds of things that affect how detailed the statement is. Besides the fact that you might be lying or telling them the truth.

Malika:

You say that details are more so on the honest side or the dishonest side.

Dr. Levine:

More on the honest side.

Malika:

Okay. So that goes with the lack of coherence, in a message, which was one of the triggers.

Dr. Levine:

There's some research that suggests that lies are actually more coherent than truths. The reason is most people aren't that concerned.

You know, people aren't little logic bots, but when liars, at least if it's an important prepared lie, then they try to get rid of the inconsistency.

Malika:

So a lack of coherence is a trigger though for TDT, but it might not actually...

Dr. Levine:

be diagnostic.

Malika:

Okay. I think, I think we're getting there. We're getting there. Okay. And then there was lack of correspondence between the content and the reality.

Dr. Levine:

And this is the best way to detect lies. So you want to be just like a journalistic fact-checker. If you can.

Malika:

Fact check. Fact check. I know that one well as a journalist myself. And then the last one I think is pretty "duh." Information from a third party warning of potential deception. And that's also a tricky one, right? Because, we don't know where this information, if this information is actually accurate or not, but it does trigger you.

Dr. Levine:

Yes.

DECEPTION AND TECHNOLOGY - NO NONVERBAL CUES?

Malika:

All right. Well, I thought it would be fun to actually have a listen back to the question which led to our meeting today. A listener, Jamie asked this question of Dr. Spottswood in episode one and her answer was read “Dr. Timothy Levine's book "Duped." So I did, and I reached out to you. So here's the question. I think it leads well into a discussion about deception and technology.

Jamie:

Hi Malika and Dr. Spottswood. This is Jamie. Thanks for having me on your podcast. My question is, how can you tell if online communication is genuine or authentic without seeing some of the cues that you might see in in-person or face-to-face interactions?

Dr. Levine:

Oh, I think it's a, this is a wonderful, wonderful, wonderful question. And the presumption is right that if you can't see those cues, this is going to hurt your lie detection. And since you've read "Duped," you know what I'll say - and I'll say that HELPS. I'm actually doing a study right now with autistic individuals.

And the hypothesis is that autistic individuals might actually be better lie detectors precisely because they can't read those nonverbal cues.

Right. So if the mismatched, if we fall for the likeable extrovert, right? But autistic people are on the spectrum don't pick that up they might actually be better lie detectors. So if reading something online, gets you to fact check rather than rely on demeanor, you should be better at lie detecting.

Malika:

I have to follow up with you on the results of this study. Wow. That is so interesting. Okay. So now let's shift in to the more narrow topic - a discussion of digital deception. I did a little bit of reading and also took some notes from a class that I took in communication and technology. In this class she basically broke digital deception into a few different parts. So there was identity-based deception, which is deception about who you are, saying you're something that you're not, posing as someone else. She quoted a study by Utz in 2005, where they found that women reported using identity-based deception for safety reasons, whereas men used it primarily for self-disclosure reasons.

And she also cited Terkel in 1995 that pointed out that it's easy to assume a new identity online because of anonymity and so many different ways to interact with people. And then you have message-based deception, which is the content of the message is deceptive. And then my favorite is "butler lies" just because I liked the name, but it's when people use technology to put off communication and they can be temporal or about timing.

Yeah. So, "oh, I just saw your text, sorry." You know, they can be lies about the activities. "Oh, I'm on another call. Can I talk to you later?" Or they can be lies about location "I'm on my way." And you're really just feeding the dog still and haven't even left the house. So how do the affordances of computer mediated communication contribute to the issue of deception? We've got identifiability. We've got persistence. We've got accessibility.

IDENTITY DECEPTION

Dr. Levine:

I think that online probably facilitates identity deception. So right before my book came out, titled "Duped," there was another book by the same title by a New York Times journalist who found out that the guy she was about to marry was basically an imposter. And it was this huge identity deception, real-life catfishing without the internet. And I think probably because you can control the timing of the message, identity deception's a lot easier online and in a lot of gaming formats, if you're, role-playing, that's pretty close to identity deception. So I think probably online things facilitate identity deception.

Malika:

You mentioned that in your book, when you said that you're a gamer and that you took on a female avatar and never thought that that was deceptive because you're role-playing, but then the person you were playing against was a female. When she found out you were a male, you felt like, Ooh, she may have felt like that was deceptive.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah. So I, I didn't even, I wasn't trying to be deceptive. I was just playing a game, but it's good to keep in mind that there's always two sides to an interaction.

Malika:

This is true. With communication we always have to think of the receiver.

Dr. Levine:

And of course, once I found out that there was misunderstanding there, I quickly, made that right.

Malika:

You know, I feel like there's a lot of opportunity also for deception when it comes to online hackers, phishing scams, and you were talking about the timing that it's asynchronous, so it's not happening in real time, at the same time. You can wait a while to craft a message and respond to someone, or you can send out a message and who knows when it's being received, but it also feels like there are endless ways to fact check or detect inconsistency.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah. So it's a pro and con - the internet lets us fact check like never before. Those of us who have somewhat public lives… you can find out a lot about me in 10 minutes online I'm pretty sure and it would be, it would be almost impossible for me to pull off identity deception.

Malika:

You could be someone you're not, you could steal, you could catfish, you could steal someone's identity and use a pseudonym?

Dr. Levine:

Yes, I could try. With anybody who had any kind of knowledge of me could Google and out me pretty quick.

Malika:

Yeah, well, and that is the good side, right? Is that you need to be triggered from your truth default in order to then take the steps to identify and try to detect if there's deception actually going on, because there can be really big consequences online.

People have lost all of their money, or as you were saying, you know, people have been catfished. Manti Teo who was engaged to someone he'd never met and found out it was not the person that he thought it was. So there can be huge consequences and we need to be able to detect those types of deception.

Dr. Levine:

And while the nonverbal cues don't really work in detecting deception, I think there are some online cues that are much more useful.

For example, there's a phishing attempt that repeatedly happens in my university and the scammers what they do is they go to the university website, and they make a note of me cause I'm a department chair and they find the professors who work under me and they create a fake email, something like Timothy Levine… you're nodding. You know this one. TimothyLevine837@gmail.com. And send my employees a message saying, Hey, I need to get in touch with you.

And what they're trying to do is they're trying to get their university log in material, because if they can get that, then they can change the routing on their direct deposits and deposit their paychecks into banks.

But it's really easy to tell if you just look at the email address. So there's this really diagnostic cue there that if you know, you look for this, then you can realize that it's fraudulent. But if you just quickly spur the moment reply, then you can get duped.

Malika:

That's what they're trying to do. That's why they use those subject lines that alarm you, "urgent!" you know, I've received those types of emails from my boss. It was not my boss. Usually they're detected pretty quickly. And someone sends out an email. I actually was just, it was mandatory for everyone at KITV4 to take a cyber training. It was fabulous. I learned things. I feel like I'm pretty astute when it comes to identifying when someone's trying to deceive me online and trying to get information out of me, but I learned new things from this training.

So it's great that, that type of thing is occurring now. We need the education to be able to identify the different ways that people are finding to try to deceive us and those really negative consequences.

BUTLER LIES

Dr. Levine:

Can we, Can we get to Butler lies really quickly?

Malika:

Yes, yes, please!

Dr. Levine:

So I called them in "Duped" avoidance lies and they are a really super big category of deception.

So maybe 20% of lies fall into this category where somebody asks you to do something, and you don't want to do it, and rather than say, you don't want to do it, you make up some excuse and it's just super ubiquitious.

Malika:

But, it's still deception.

Dr. Levine:

Yes. I don't think it's a bad, it's not a bad deception.

Malika:

I think that's where, where we feel uncomfortable about it, you know? Ah, but I'm doing it for good reasons, I'm trying to maintain this relationship, and not have an awkward conversation and keep the, they don't need to know.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah, it's also really common, like with work events. Right. So, you know, In my job, there's all these events I'm supposed to go to. And sometimes it's just too many, but I'm not going to tell my boss, “no, I don't really want to be a good citizen today,” which is the truth, you know? I'm going to say, “I'm sorry. I have a previous engagement.”

Malika:

And in the book, you also mentioned how there are certain lies that we just in society, it's kind of a norm for, for example, for women to underestimate their weight and things like that.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah. It's an interesting discussion with new media researcher, Joe Walther about this on, on whether it's even deception or not, or do people just know that if, if somebody says this, you should just tack off five.

Malika:

Yeah. I mean, I would venture to say that that's pretty normative. If you're online and oh yeah, add this many to a female minus this many pounds for a male.

Dr. Levine:

If it's something that should be understood, it's really not deception according to the definition we talked about in the beginning.

Malika:

That is interesting. Lots to think about. I thought now we could transition into a question from a listener. Are you ready? This question comes from Ian.

LISTENER QUESTION FROM IAN

DOES THE TYPE OF RELATIONSHIP YOU HAVE WITH A PERSON HELP OR HINDER DECEPTION DETECTION?

Ian:

Thank you for having me on the podcast. We all sort of have an internal BS meter. For example, if I think poorly of a person, I already might assume that they tell half-truths. When it comes to strangers. I kind of use my objective BS meter, with a loved one, emotions come into play. So my question for you is, does the type of relationship you have with a potential deceiver impact, how accurate your deception detection is?

Dr. Levine:

Good question. And this is something the research really hasn't sorted out too well yet, and there's conflicting points. I think the research is pretty clear that we all overestimate the quality of our BS meter. We all think we're a little better at it than, than we actually are. This of course doesn't apply to me, but everybody else - a little sarcasm there.

So the first research really to get at this was my good friend, Steve McCornack. What his research found was the closer your relationship, the more you tend to trust the person and the more you think you can tell, and then the more likely you are to miss lies. So being close to somebody indirectly reduces lie detection because we have knowledge of the other person and we know things about them.

This can also make lie detection easier. For example, there's no way I could lie to my wife about my political beliefs because she knows what my political beliefs are. So the more we know and the more history we have with people, the less things we can lie about because they already know. And similarly, the more interconnected we are, because one of the big triggers is information from other people.

The more integrated we all are in a social network, the more small town, our little group of people are, this also limits what we can effectively get away with on deception.

So relationships and lie detection can work both ways when we can be motivated to believe the person or want to believe them. And we've all had the experience with the friend who's being deceived by a romantic other, and we try to warn them. They're not having it until usually it doesn't end well, but at the same time, our knowledge of other people gives us factual knowledge that lead to better lie detection.

Malika:

That's so interesting because you might not want to find out that they are lying. And so maybe you don't take those extra steps to do the fact- checking, you're hearing it from the third parties and you, maybe you feel a little something, but your, your goal is not to end your relationship. And to find out that you're being deceived, you know, self preservation again.

Dr. Levine:

So one of my first studies of deception, I did with one of my students at University of Hawaii when I was on the faculty there, and it was never published, but the study was this - I asked a sample of community college students and a sample of people in a senior home, if your significant other was lying to you, would you want to know? And the community college students were all like yes. And the senior citizens, were all like no.

Malika:

Interesting. And why did you think that happened?

Dr. Levine:

Well, if you have a very long-term relationship, right, you have a huge investment in not wanting to know. It would be really disruptive to your life. But if you have a relatively short-lived relationship, you have much less invested, it might be good to know and get out of it.

Malika:

So interesting. Oh my goodness. Well, I could speak to you forever, but as we round out our time here together, could you give us some research-based communication tools that listeners can use to detect deception in online or in normal communication? And what should you do if you suspect deception?

Dr. Levine:

The best thing you can do to detect deception is simply try to fact-check trying to triangulate with other sources of information. If you can't do that, assess plausibility, does it sound reasonable? The third thing I would suggest is ask yourself, does it matter? Because if it doesn't matter, who cares.

You know, if it does matter, then invest time in, you know, if you're making a big investment decision or you're going to make a big commitment or something, that's one of life's big decisions, do a little research, but a lot of deception like avoidance lies or Butler lies, right it's not really a big deal. Don't worry about it much because most people are pretty honest. Most of the time we're better off trusting people, and if we get too suspicious, then we second guess all the information and it makes it hard to learn anything new and it makes it hard to have relationships with other people. So we're better off trusting other people unless there's good reason to want to do some little self-protective behaviors.

Malika:

If there's a trigger.

Dr. Levine:

Yeah. And even if there is a trigger don't presume bad, just try to look into it open-minded.

Malika:

I like that advice. That is great advice, Dr. Levine, is there anything else you'd like our listeners to know, or you think that they'd be interested to hear?

Dr. Levine:

I think we did a pretty good job covering things.

Malika:

All right. Fabulous, well, thank you so much for your time. When I was getting my Bachelors, this theory wasn't yet presented, so I learned about nonverbals. I loved your book, very detailed, and it was nice to learn about your theory and hear the research behind it and how it's applicable to everyday life. So thank you so much.

Dr. Levine:

Let me just mention that, I've started a conversation with my publisher. “Duped,” might not be for everybody, it is pretty academic. Before you'd go out and buy it, read the reviews on Amazon. They're pretty good.

Malika:

Are you trying NOT to dupe people?

Dr. Levine:

I'm trying not to dupe people, but I'm talking to my publisher about maybe writing a follow-up called "Duped Again" that is much more accessible, so much more for a public audience. Whereas "Duped" was my big kind of story of my career, laying out the theory and laying out all the research, but "Duped Again" if it happens, will be much more along the lines of our discussion here.

Malika:

We will keep an eye out for that. Definitely, there's a lot of numbers. I got the gist of it and I did learn so much. And I understand why you went into detail on each of the, what is it, 60 + experiments that you did because there is a process that you undertook that was very methodical and very detail-oriented to get to this place of presenting a theory. It's not just. (snaps fingers). Dr. Levine, thank you so much for your time. I am just beside myself that I got to sit with you and I love that there's the Hawaii connection.

Dr. Levine:

Very cool. I had a blast. Thanks for inviting me.

References

Dr. Timothy Levine’s Google Scholar Profile with links to all of his research

Dr. Steven McCornack’s Google Scholar Profile with links to all of his research

Turkle, S. (1999). Cyberspace and identity. Contemporary sociology, 28(6), 643-648.

Utz, S. (2005). Types of deception and underlying motivation: What people think. Social Science Computer Review, 23(1), 49-56.

The YouTube version of Episode 6:

Duped - Can you tell if someone is lying? We break down the deception research with Dr. Timothy Levine

Giveaway Details

This is one of the marketing strategies we are using to give the podcast that extra little push.

Any participation is GREATLY appreciated!

Here is a list of the giveaway items that I have already secured:

Olukai footwear x 2 ($100 value each)

Maui Divers pearl and diamond pendant ($695 value)

Noho Home luxury quilt ($200 value)

Aloha Modern luxury towels

Goli Gummy 6 month supply of vitamin gummies

Lehualani jewelry

Chef Sheldon Simeon’s Cook Real Hawai’i cookbook

Primally Pure mist, serum, and mask

Cameron Brooks photography prints x 5

Oneloa Maui hat, clutches

$100 Amazon gift cards x 4

5 Proact Products Hawaii small solar lights

Samia Surfs Children Book

Tidepool love hair picks

Radar Girls by USA Bestselling author Sara Ackerman

Goodwill Hawaii $100 gift certificate

Each of these actions counts as one entry:

Follow @communificationpodcast on Instagram

Follow @malikaspodcast on Twitter

Follow @communificationpodcast on Facebook

Share the @communificationpodcast on any social channel (tag me @malikadudley so that I can count your entry)

Sign up for my newsletter (you can do that in the sidebar here on this web page, on the home, or about pages)

Leave a comment on the YouTube channel podcast episodes.

For FIVE entries: Write a review for the podcast – share it on social media and tag me so that I see it

**This giveaway is open to anyone in the United States. Winners will be randomly selected and announced on the last day of each calendar month. Details on number of winners, and who has won will be announced on @communificationpodcast social media channels. We will allow one week for a response, after which time a new winner will be selected. This giveaway is in no way associated with any of the social media channels mentioned above. No purchase necessary, void where prohibited. By entering, entrants confirm they are 18+ years of age, and release any of the social media channels mentioned above from any and all responsibility.**

Current and future episodes of the Communification Podcast

Click below to see the show notes & listen in.

The episodes that have yet to drop are COMING SOON!